The question that sparked this post is: whose mandate is it to collect information?

A few weeks back our team attended a meeting with Plan Kenya and partners who are using mapping tools for generating information. Someone in the room asked:

“Whose mandate is it to collect information?â€

The meeting was called to discuss a specific tool data collection tool called POImapper, which is being developed by a Finnish company called Pajat. Plan Kenya is piloting the tool and has developed custom data collection forms to collect data to inform Plan’s work in Kilifi. There is no question about mandate when gathering programmtic level data (about children benefiting from Plan’s sponsorship programme for example). The concern raised during the meeting was about an organization collecting public information in an area where government should be providing this information – this includes the base level information on roads, schools, and other public infrastructure.

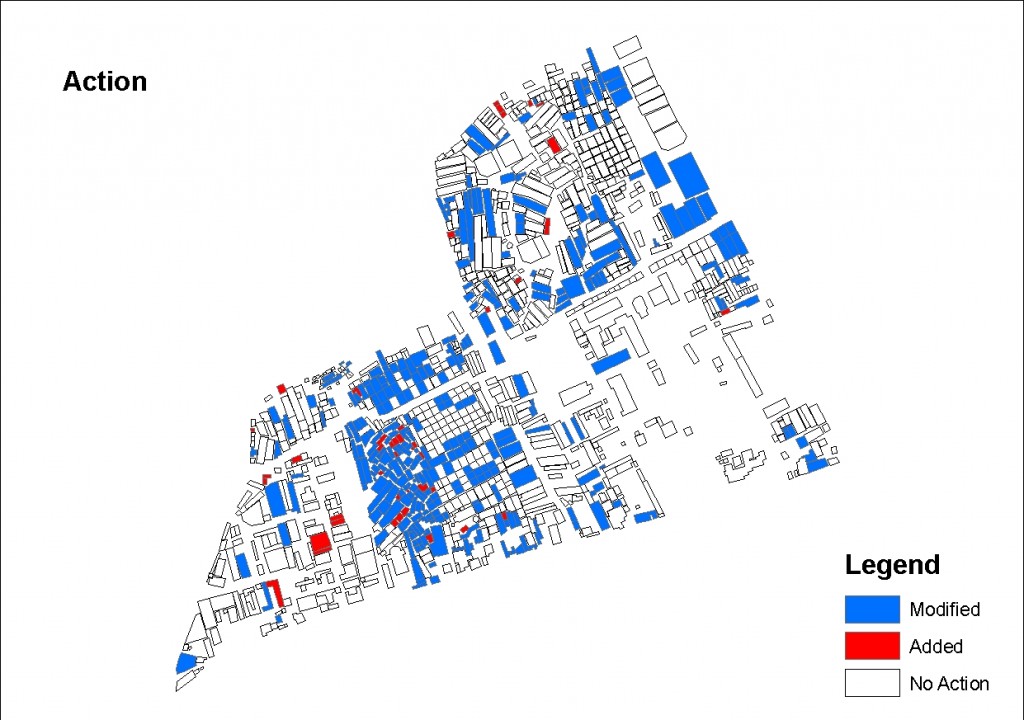

One of the major challenges of using POImapper however is the lack of base maps upon which to overlay the Points of Interest (POI). Without good base layer data, it is difficult to discuss the implications of the information being collected. Pajat and Plan Kenya made the decision to switch from Google Maps to OpenStreetMap because of this challenge (through our work with Plan Kenya, we also hope we played a part in this decision). With OpenStreetMap, the organizations are free to improve the base layer information as necessary and use the data in their (for-profit) portal. But this brings up the question of mandate? Should a non-governmental organization (NGO) really be doing this work?

The question about mandate got me thinking about how government, citizens and organizations collect and share (or don’t share) information.

The question “whose mandate†gets at the question “whose information is this that we are collecting?â€

One point of view (shared by some at the meeting) is that information is the property of the government. The government is mandated to collect and disseminate information for the public good. Others should not interfere. There is validity in this point of view.

Access to information is in the Bill of Rights of the newly adopted Kenyan constitution. “Right and fundamental freedom†number 35 in Chapter Four, Part 2 states that:

35.      (1) Every citizen has the right of access to—

(a) Â Â Â Â Â Â information held by the State; and

(b)       information held by another person and required for the exercise or protection of any right or                           fundamental freedom.

(2) Every person has the right to the correction or deletion of untrue or misleading information that affects                 the person.

(3) The State shall publish and publicise any important information affecting the nation.

The government is constitutionally mandated to grant any citizen access to “information held by the State.†The government is mandated to go even further and not only publish “important information affecting the nation†but must also publicise this information (theoretically improving accessibility).

But the reality of the situation is the governments don’t always do what they are mandated to do. Sometimes governments need a push in the right direction – a reminder of their role and their responsibility to the citizens of their country. The government may also need a “proof of concept†– a demonstration that there is an easier, more cost effective and efficient way of delivering information and services to citizens.

One example would of a “proof of concept†is the use of ICT in universal birth registration in Kenya, being piloted by Plan Kenya in Kwale.

On the Plan Kenya country website for this campaign it states

“It is government policy that every child should be registered at birth, and this is covered by the Births and Deaths Registration Act. However, there is a huge gap between law and practice. Birth registration is not fully decentralised, and so families have to travel long distances, particularly in rural areas, to access registration services. The birth notification process – through which parents complete a notification form at the chief’s office when a child is born, which are then submitted to the district registrar of births – can take more than a year or even two. Any registration after six months of birth is considered late registration, when the process is more complex and lengthy, and there is also a penalty – which act as deterrents to the registration of children. Parents also do not see the need to register their children and so do not actively seek out registration services. The government is reviewing this Act, which we hope will ensure greater access to registration services for Kenyans.â€

Instead of waiting for the government to improve its birth registration system, Plan Kenya is working together with local government to digitize the birth registration system.

This is a success story of a local government partnering with an NGO to achieve results. It is also why we have advocates – advocates for access to essential medicines, for improved service provision, for freedom of the press, and the list goes on.

In this case of improving access to information generally, we need information advocates – those citizens and/or organizations who advise individuals and organizations on the importance of information, where it can be accessed and how it can be utilized. Information advocacy is similar to info-activism, but does not specifically target activists or advocates. Information advocates raise awareness about the importance of information more generally.

Should international, national or local NGOs information replace the need for government information? No, indeed NGOs should not. Organizations and advocates should work closely with government to advise and improve systems for collecting and disseminating information. It is government policy, in many countries to provide access to information. Governments and NGOs need to work together to open up information and make it accessible for local populations

I must admit that the Map Kibera team is biased toward open knowledge and/or open data. We have a commitment to open data. We create, share, and advocate for open information, in all sectors (NGO, government, citizen). The disclaimer is of course that not all data should be made public – for example private data that may endanger individuals or invade privacy should not be made public (such as precise locations of individual vulnerable children or families, individual level health information, etc). Aggregate information of this kind may however be useful for planning and advocacy purposes.

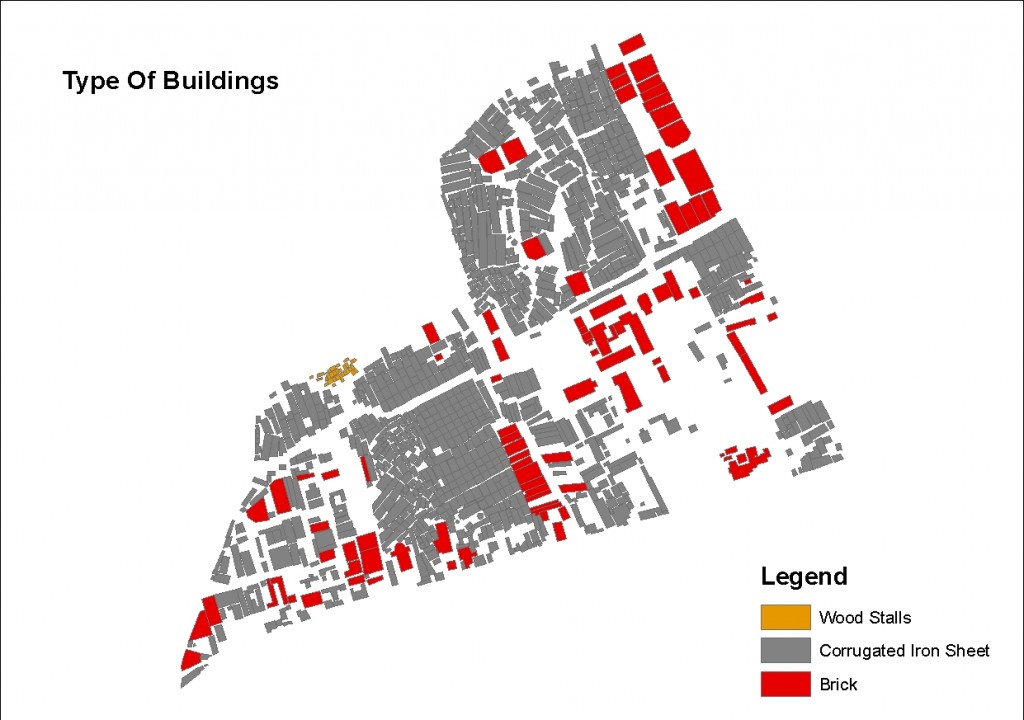

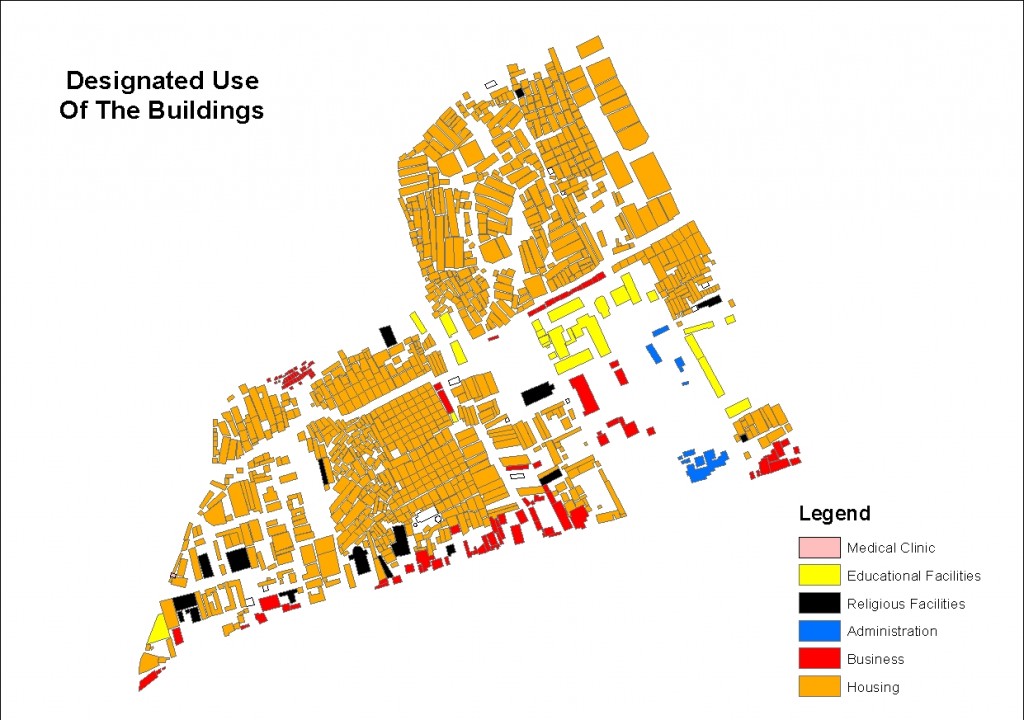

We do focus on public information – that is information about services that are open and available to the public – such as water access points, sanitation facilities (toilets mainly), schools, health clinics, shops, kiosks, restaurants, bars, and many more. The teams in Kibera and in Mathare are working hard to integrate information into local government channels.

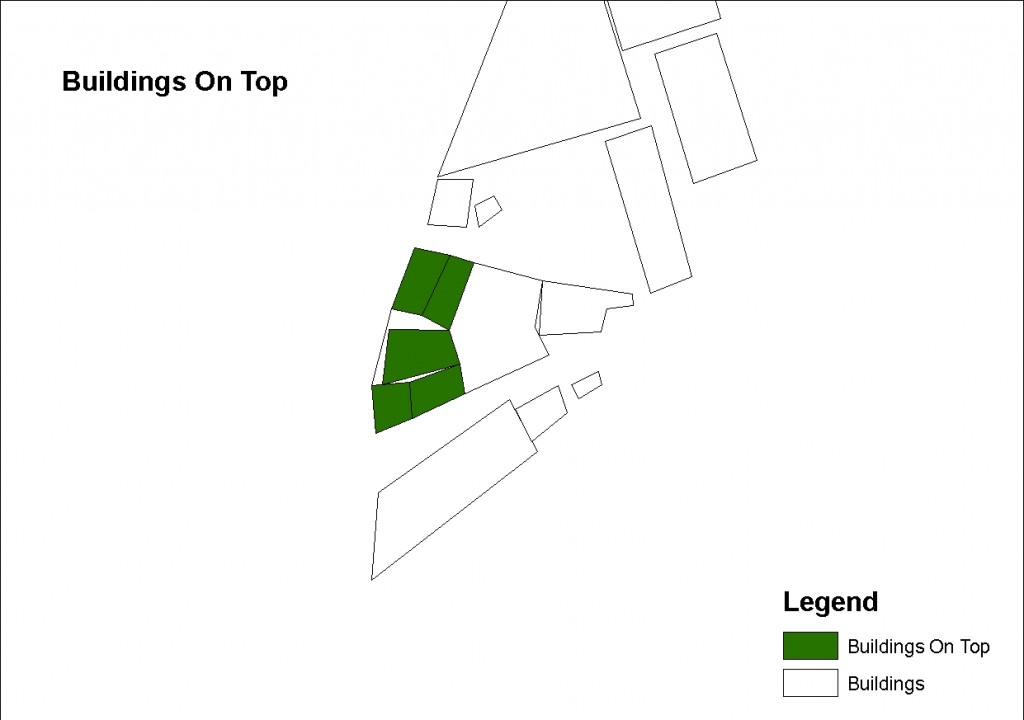

Demand for open government data is increasing around the world. Kenya is not unique in terms of challenges in opening up government data. In Kenya there is however very little data available at the local level. Through visits to City Council and local authorities in Kibera and Mathare, we’ve learned that the local area counselors, chiefs, District Officers, District Commissioners, and other officials do not have access to maps of their areas. The local government authorities may need some support in terms of generating baseline information (including maps) of their constituencies. This is not a criticism of the government, but a call for NGOs, citizens and government to work together to generate and share information for better planning and development. This is a major challenge, but our teams are consciously working hard to open dialogue with local government to create sustainable systems of information creation and dissemination. Plan Kenya has been an invaluable partner in terms of advising and supporting this process. Keep your eyes out for updates on the work in Kibera and Mathare.

[Cross posted on my blog]