10 years ago Erica Hagen and I were getting ready to start Map Kibera. I read Planet of Slums, was buying laptops on the way to the airport after Crisis Mappers, getting excellent guidance and connections from Ushahidi, and feeling completely overwhelmed. Before we even started, the project was being celebrated in the global media. Heading to Nairobi’s largest slum to make a map. What had we signed up for? I’m looking back on the experience myself now 10 years on, after 6 weeks in a much changed Nairobi.

10 years ago Erica Hagen and I were getting ready to start Map Kibera. I read Planet of Slums, was buying laptops on the way to the airport after Crisis Mappers, getting excellent guidance and connections from Ushahidi, and feeling completely overwhelmed. Before we even started, the project was being celebrated in the global media. Heading to Nairobi’s largest slum to make a map. What had we signed up for? I’m looking back on the experience myself now 10 years on, after 6 weeks in a much changed Nairobi.

It’s way way more than I ever imagined. We intended to stay for a month. Through muddy days and very spotty internet, the map took beautiful shape. Zach Muindre and Lucy Fondo and 11 more young people from the 13 villages of Kibera got excited about mapping. That was never going to be enough. That map by itself did not do enough for the people of Kibera, and we felt a deep responsibility to see this work through. We wanted to make the connection to change, for the order and chaos, invention and despair, that city within a city, Kibera. To keep putting the people of the Kibera community in the driving seat on what data was important to them and how it should be used. That impulse quickly inspired citizen reporting and data journalism, with Kibera News Network, still led by Joshua Ogure, and Voice of Kibera.Â

I wrote this in 2013:

In all honesty, the work Map Kibera has set for itself is extremely difficult, steps beyond what is normally attempted, and we have had our share of bumps and scrapes. But anything worth doing takes patience and perseverance, adaptation and learning. We carry on, and we’re ready for what’s next.

Building a team. Mapping and mapping again. Telling stories. Bringing together people to think about data and place. Training and riding the wave of new technologies. Putting maps on walls. Taking the world’s biggest and smallest stages. Fundraising and reporting. Strategic plan after plan. Building several versions of organizations. Advocating to government. Argument. Stress. Triumph. Sometimes all in the course of one day.

After 10 years, has Map Kibera changed Kibera? Yes there’s been significant contribution over the decade in Kibera. And around the world. We’re certainly not done, 10 more years for sure. It’s certainly hard to assess the impact of 10 years. Here’s a few ways I look at it.

Personally, I’ve carted recovered organization documents in a wheelbarrow across Kibera, fended off local youth looking for payment for “securityâ€, waited for ages for a government official to sign a letter, met with ambassadors, and a thousand other unique experiences I never would have had otherwise. I got to know a unique place well.

There’s the data. I’m not going to try to quantify it, but it’s both wide in location and deep in the detail collected. Kibera was mapped and mapped again. Almost all of the slums in Nairobi — Mathare, Mukuru, Kangemi, and others — mapped. Outside of Nairobi, cities and rural areas across Kenya, from Kwale to Baringo, have been mapped. Not just mapped, but mapped by and for community members in each of those places. And the places in between, by the OSM community, inspired and connected by Map Kibera’s pioneering work. All of this data within the infrastructure and community of the global OpenStreetMap project, the foundation of all this work.

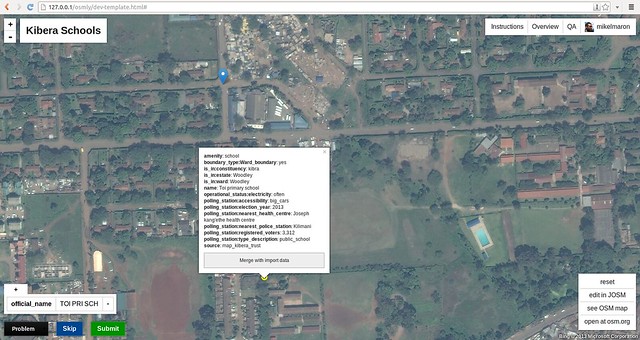

It took 3 years for me to feel at last satisfied that Map Kibera had an impact in Kibera itself. It takes at least that time to build trust, to show that an effort is not a flash in the pan, and figure out exactly how something as abstract as data and maps can make a contribution. The 2013 election saw mapping for peaceful elections, building strong networks, distribution of maps within the community and to security services and government, debates and interviews with candidates, monitoring and reporting through all phases of the election — from registration, primaries, campaigning, elections, results, and follow up — after the national and international media left. It made a difference. Voice of Kibera and Kibera News Network really found their stride, reporting from polling stations, and doing video interviews with candidates. OpenSchoolsKenya brought visibility to all kinds of schools in Kibera (and Mathare and Kangemi), that parents, teachers, administrators, and government lacked. Kibera is currently mourning the loss of MP Ken Okoth, who championed the work of Map Kibera and put schools data to work to successfully advocate for more educational resources. There were many other projects that had an influence on water and sanitation, health, food security — their impact less visible, behind the scenes. This data has been used by organizations large and small to orient, track and ground work in all these places. We know of some of them, but so many more we have no idea about because the maps are open to all.

Male erection is a complex process. It involves the male brain, nerves, hormones and blood vessels. Erectile dysfunction may indicate a malfunction of any of these elements. When you are going to start taking Cialis 20mg tablets, consult with your doctor first and inform him about your health issues. And stop taking Cailis immediately if you feel not good after intake of this medication. Erectile dysfunction is an indicator that one of these systems is malfunctioning and may be a disease.

All of this progress requires money and an organization. From JumpStart International’s small bet on us at the beginning, to Unicef, US Institute of Peace, Hivos, Omidyar, Plan, Indigo Trust, World Bank, Map Kibera has had the attention and resources of international development. We are deeply appreciative. And deeply challenged. Matching a project rooted in grassroots community to global development has not been easy. The project cycles and organizational expectations don’t fit long term community development. Looking back now on countless proposals, work plans, reports, strategic planning sessions, organizational charts. And we did not come to this experienced in building organizations, and made our biggest mistakes in misapplying parts of models of a worker’s cooperative, community organization, traditional NGO, and company, lately finding stride in a combination of those. For the past 5 years, Erica has focused so much effort to pull this work together, as have Joshua and Zack, who have devoted themselves on a day to day basis well beyond the call of duty to keep the vision alive. Map Kibera remains deeply focused on Kibera, while being the leading organization for developing community mapping across Kenya, as well as globally networked and linked. It’s not easy to connect a grassroots community effort to a global perspective and industries. I think they’ve finally found an operational groove 10 years on.

Around the world, Map Kibera became an inspiration for a new kind of community mapping, one that was simultaneously rooted in community development, and also integrated into the global data infrastructure of OpenStreetMap. Map Kibera has served as a template and model for countless other projects. As Erica and I began our return trip to Kenya in January 2010 to work with Map Kibera for another year, Haiti was struck by an earthquake, and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s first effective activation began. After many stolen early morning moments during our “vacation†coordinating the Haiti response, I helped plan post-emergency activities of HOT on the ground in Haiti, modeled directly on Map Kibera. The Map Kibera team also started the OSM mapping effort in Dar es Salaam, in Tandale, which has now covered the whole city of Dar for flood risk mapping. It was our mapper Lucy, still a key Map Kibera team member, who traveled to Dar to train communities in OSM back in 2011. Regularly, even just last month, I hear from people starting mapping projects inspired by Map Kibera.

This influence flowed from an incredibly strong story — young people putting this large and famous and yet “invisible†settlement on the map. Map Kibera has been profiled by CNN, PBS, New Scientist, National Geographic, Wired, Al Jazeera, Le Monde, and The Guardian. It’s taught in schools, every geography undergrad seems to watch The Geospatial Revolution — it’s even a part of on-boarding for some teams at Mapbox. Map Kibera has been featured in the Smithsonian and other museum exhibits, in popular science books and coffee table books of critical cartography. It’s been referenced in hundreds of research publications. Though I happen to believe the best research on Map Kibera has been done by its practitioner, with Erica authoring good pieces early on for MIT, and more recent learning retrospective for Making All Voices Count. Erica has told the Map Kibera story on the TED Stage. I’ve shared in Seoul, Zach has presented in Hyderabad, and Josh everywhere from New York to Azerbaijan.

But ultimately, the best way I know to track the influence is in the people we’ve gotten to work with. Impossible to name them all. Some have come and gone, and some have stayed all the way through — Zach and Lucy are still mapping, training government officials, and leading the roll out of projects. Josh is the general manager and has brought KNN to a level on par with professional news agencies, along with Steve Banner and Jacob Ouma, who also have been with us from the early days. They are now as old as I was when this all started. Erica — who dropped everything to come to Kenya with me, then married me, and who has put everything into continuing the effort even after my attention has gone elsewhere. Unbelievable to think back to the 13 young kids who took a chance on this crazy project.Â

So we’re going to celebrate and I hope to see everyone. Map Kibera is throwing a party tonight, August 16 to celebrate the first 10 years, and 15 years of OpenStreetMap. Find the details here and let is know if you’ll join us to raise a glass to 10 years of Map Kibera.